The Ancient Egyptian Footwear Project (AEFP) is a multidisciplinary, ongoing research, consisting of the study of archaeological artefacts and their (museological) context, iconography, philology and experimental archaeology and, where appropriate, ethno archaeology in order to better understand footwear’s meaning and position within the ancient Egyptian society. An important aspect is to explore the influence of foreigners (Nubia, Near East, Mediterranean) on Egyptian footwear and, in a broader perspective, leatherwork. Moreover, the project aims to function as point of reference for future research. (Text adapted from Tutankhamun’s Footwear. Studies of Ancient Egyptian Footwear)

Methods [spoiler]

The basis of the research is the study of the archaeological finds (phase I). One can only understand an object and put it into context with a thorough knowledge of the manufacturing technology and its development. Phase II will deal with philological and iconographic information. Although phase I is still in progress, the textual and iconographic work has already begun. The thus obtained information will, if necessary, be checked by experimental archaeology (which makes up phase III, together with ethnographic information): the remake of objects not only gives insight in the manufacturing techniques but the reproduced pieces of footwear allows us to study for example wear. Finally, anthropological data is needed to see, amongst others, what the consequences of going barefooted are and whether we can recognise this in the archaeological record. Moreover, it will give insight in the size of footwear.

The information of the AEFP will be combined with the results of the Ancient Egyptian Leatherwork Project (AELP), the project of which includes experimental archaeology and chemical analyses of skin processing/paint and pigment. In the final phase, the results will be combined and interpreted in their entirety.

[/spoiler]

Objectives [spoiler]

The objectives of the AEFP can be divided in two groups: the material culture (I) and socio-cultural aspects (II).

I) The material culture consists of three components, addressing questions on the kind of materials (origin) and its processing before being turned into footwear (such as harvest and preparation). The second part will deal with the manufacturing techniques (e.g. stitching and coiling), the decoration (e.g. pigment/paint, appliqué work) and typology. Other characters, which are not part of the material culture per se, for example dating, will be ultimately included. The third part deals with the sandal-makers and their workshops, including the tools. What do workshops look like and how can they be recognised in the archaeological record? If we recognise them, the information obtained from such spaces and tools needs to be combined with that from the artefacts themselves to elucidate production processes.

II) Socio-cultural aspects is a rather broad and loosely defined term, which includes topics such as the interpretation of the objects, the value of footwear within the community and society at large (in both a monetary and aspirational sense) and the organisation and status of the sandal-maker. Within these focal points, there are several points of interest:

– Which status had footwear within the community? This question goes along with the question how footwear is to be interpreted. For example, tomb sandals of wood or cartonnage are known to have been made especially for the funeral but was footwear, which could have been used in daily life, also buried with the owner? Important are, obviously, the finds in the tomb of Tutankhamun, even though these can hardly be representative for the society at large or possibly even for royal burials. Tutankhamun’s footwear is also important with respect to foreign influence: closed shoes may have been a late New Kingdom (post-Amarna?) innovation brought by people from the Near East but recent research may point to a development from open shoes into closed shoes (Veldmeijer, 2009f; In press c). Indeed, it has been suggested that Tutankhamun’s shoes are imported but these statements are not based on thorough research.

– Sandal-makers are known from literature but how specialised was this profession? If referred to them, it is to those who produced leather sandals. Was this the same person who made other leather objects? And who made the fibre footwear: did the basketry maker produce sandals as well since the techniques of manufacturing fibre sandals partly overlapped with those of basketry? How are we to explain the absence of manufacturing of shoes in representations (and the near-absence of depictions of shoes in general), whereas there are many examples known from the archaeological record and several texts mention ‘enveloping sandals’ (interpreted as ‘open shoe’). What was the status of the sandal-maker and other people involved in this process?

– How specialised was the craft of footwear manufacturing? Some types of fibre footwear do not seem to require specialist knowledge: could the people themselves have made these? Others, however, seem to have been made by professionals. Some of the footwear from Tutankhamun combines several materials, indicating that different craftsmen were involved: how was this organised?

– How are we to explain the differences in detail? Are these due to regional differences and/or different production centres? Could, for example, the differences be explained by fashion or status or a combination?

– Can we distinguish footwear for certain groups within the community? There are indications that royals wore other footwear. Also, texts refer to sandals for priests as well as sandals for men and women. We also know that children wore sandals: are these different, except, of course, for their size? What exactly are these differences? Closely related to these questions is how footwear was used. Can we recognise long-term use? Wear patterns as well as (extensive) repair gives much information. Could footwear be worn anywhere and at any time, a question that is closely related to symbolism. How are we to interpret the differences (if there are differences) if it comes to gender, religious scenes and wearing footwear inside or outside buildings?

– On a less limited scale, we see that there are clear differences in footwear from Egypt, Nubia and the Near East (likely also the Mediterranean). We are fortunate, not only in having a large corpus of finds from Nubia, but with the preservation of possible Persian footwear (Elephantine) as well (Kuckertz, 2006; an update of this publication is forthcoming), the latter of which differs considerably from the Egyptian (and Nubian) footwear. Moreover, foreigners are depicted relatively often (in Egypt as well as in their own countries) with footwear. How was Egyptian footwear influenced by this foreign footwear and if it was, how did this manifest itself? Can we detect differences on a more limited geographical scale, i.e. from one settlement to another?

– The shape of footwear changed through time (but also other features, such as material and manufacturing techniques). By mapping this in detail a good insight can be obtained in the development (typology) and consequently, footwear might serve as an aid in dating. This, in its turn, could enable us to date footwear in collections of which the context and date are unknown.

– In some cases, information can be obtained on the demography of the settlement. What does the footwear tell us about its owner and about the inhabitants of the community at large? What can we say about the relative wealth of them? Especially important for this question are the finds from Amarna, Qasr Ibrim and the Coptic monastery Deir el-Bachit, all of which are included in the AEFP and AEFL.[/spoiler]

Typology [spoiler]

There are several typologies of ancient Egyptian footwear, most of which are based on a limited number of archaeological objects. Gourlay (1981a: 55-64; 1981b: 41-60) published a typology based on the material from Deir el-Medinah, making distinction between cordage sandals, sandals from palm/papyrus etc., and leather sandals. Although distinction is being made between sandals with an upper, they are regarded as a type of sandal (Ibidem: 61-62) rather than open shoe, despite the remark that the Type A sandal is turned into a shoe by adding an upper. Montembault (2000) has based the typology on the material housed in the Louvre, but most of the material is unprovenanced. Consequently, geographical information as well as date plays at best a marginal role. The typology developed by Leguilloux (2006) is more detailed and includes dates, but is based on the material from Didymoi, a Roman caravanière along the Coptos-Berenike route in Egypt’s Eastern desert only and is therefore of limited use for Pharaonic footwear. In both typologies, the emphasis lies on the development of shape.

Goubitz et al. (2001), however, classifies European footwear on the basis of the fastening or closure method, which is used in the AEFP too. However, they note that in their work this “is not always consistently applied. In such cases priority has been given to recognisability.” (Ibidem: 132). This method is followed by the AEFP. Using technological features, such as fastenings, and recognisability often goes hand in hand but this relation is stronger in sandals than in shoes. With shoes, this is different, as in appearance comparable shoes can be made in different ways – for example with or without rand (not present in early Egyptian footwear). This, in its turn, can be originally designed but can also be due to repair, the exact origin of which in many cases cannot be determined anymore. Furthermore, the appearance of a shoe is important, evidenced for example by the fact that inserts are always placed in such a way that they are hard to notice. In sandals, a good example for the same technology but different shapes is some types of sewn-edge plaited sandals and fibre composite sandals.

The AEFP first makes distinction, of course, between sandals, shoes, boots etc. made with different materials. These groups are divided into Categories, the differentiation of which is based on the materials in combination with manufacturing technology (for example fibre, sewn sandals, leather composite sandals etc.). These categories are, if possible, divided into Types, for which different criteria are used depending on the category. Finally, types can be divided into Variants. A typology should offer insight into the development of footwear, which can only be done after the incorporation of a large sample of, preferably, all periods of Egypt’s history. Moreover, dates as well as geographical distribution (provenance) will be incorporated. Since the first phase of the AEFP mainly deals with the manufacturing technology, these missing criteria will be investigated and incorporated in a later stage of the project.[/spoiler]

Collections [spoiler]

- Ägyptisches Museum und Papyrussammlung, Berlin

- Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

- British Museum, London

- Egyptian Museum, Cairo

- Luxor Museum, Luxor

- The Manchester Museum, University of Manchester (future)

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- Museo Egizio, Turin

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden

- National Museums of Scotland, Edinburgh

- Oriental Institute Museum, Chicago

- Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology UCL, London

- Roemer- und Pelizaeus-Museum, Hildesheim

- Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto

- Sammlung des Ägyptologischen Instituts der Universität, Heidelberg

- World Museum, Liverpool[/spoiler]

Excavations [spoiler]

- Amarna

- Amenhotep II Temple Luxor

- Berenike

- Deir el-Bachit

- Dra Abu el Naga

- Elephantine

- Fustat

- Hierakonpolis

- Mersa Gawasis

- Qasr Ibrim[/spoiler]

Researchers [spoiler]

- Director and principal researcher: Dr. André J. Veldmeijer (American University in Cairo/PalArch Foundation)

- Iconography footwear (Tutankhamun footwear project): Aude Gräzer (University of Strasbourg)

- Identification fibre: Dr. Caroline R. Cartwright (British Museum London)

- Experimental archaeology: Prof. Dr. Salima Ikram (American University Cairo)/Lucy Skinner/Martin Moser

- Experimental archaeology/conservation/reconstruction: Lucy Skinner (Museum of Natural History and Archaeology, University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway) /Barbara Wills (British Museum London)

- Object study (leather): Prof. Dr. Salima Ikram (American University Cairo)

- Philology (Tutankhamun footwear project): Prof. Dr. Fredrik Hagen (Copenhagen University)

External scientific advisors (mainly leather related)

- Dr. Carol van Driel-Murray (University of Leiden)

- Barbara Wills (British Museum London)

- Archaeological Leather Group, England

Artists/photographers

- Ing. Erno Endenburg (PalArch Foundation, Amsterdam)[/spoiler]

Publications

See http://www.leatherandshoes.nl/andre-j-veldmeijer-cv/.

Footwear Bibliography Overall (in preparation) [spoiler]

Alfano, C. 1987. I Sandali. Moda e Rituale Nell’ Antico Egitto. – Città di Castello, Tibergraph Editrice.

Bénazeth, D. & C. Fluck. 2004. Fussbekleiding der Reitertracht aus Antinoopolis im Überblick. In: Fluck, C. & G. Vogelsang-Eastwood. Eds. Riding Costume in Egypt. Origin and Appearance. – Leiden, Brill: 189-205.

Driel–Murray, van, C. 2000. Leatherwork and Skin Products. In: Nicholson, P.T. & I. Shaw. Eds. 2000. Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology. – Cambridge, Cambridge University Press: 299-319.

Friedman, R. 2007. The Nubian Cemetery at Hierakonpolis, Egypt. Results of the 2007 Season. The C-Group Cemetery at Locality HK27C. – Sudan & Nubia 11: 57-71.

Goubitz, O., C. van Driel–Murray & W. Groenman–van Waateringe. 2001. Stepping through Time. Archaeological Footwear from Prehistoric Times until 1800. – Zwolle, Stichting Promotie Archeologie [used by the AEFP for its terminology].

Gourlay, Y.J.-L. 1981a. Les sparteries de Deir el–Médineh. XVIIIe-XXe dynasties. I. Catalogue des techniques de sparterie. – Cairo, L’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale.

Gourlay, Y.J.-L. 1981b. Les sparteries de Deir el–Médineh. XVIIIe-XXe dynasties. II. Catalogue des objets de sparterie. – Cairo, L’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale.

Greiss, E.A.M. 1949. Anatomical Identification of Plant Material from Ancient Egypt. – Bulletin de l’Institut d’Égypte: 249-277.

Haarlem, van, W.M. 1992. A Pair of Papyrus Sandals. – Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 78: 294-295.

Hayes, W.C. 1959. The Sceptre of Egypt. Volume 1 & 2. – New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Kuckert, J. 2006. Schuhe aus der persischen Militärkolonie von Elephantine, Oberägypten, 6.-5. Jhdt. V. Chr. – Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft zu Berlin 138: 109-156.

Lilyquist, C. 2004. With contributions by: J.E. Hoch & A.J. Peden. The Tomb of Three Foreign Wives of Tuthmosis III. – New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Montembault, V. 2000. Catalogue des Chaussures de l’Antiquité Égyptienne. – Paris, Réunion des Musées Nationaux.

Moran, W.L. 1992. The Amarna Letters. – Baltimore/London, Johns Hopkins University Press.

Nauerth, C. 1996. Karare und El=Hibe. Die spätantiken (‘koptischen’) Funde aus den badischen Grabungen 1913-1914. – Heidelberg, Heidelberger Orientverlag (Studien zur Archäologie und Geschichte Altägyptens Band 15);

Reeves, N. 1990a. The Complete Tutankhamun. The King. The Tomb. The Royal Treasure. – London, Thames and Hudson.

Russo, S. 2004. Le calzature nei papyri de età Greco-Romana. — Firenze, Istituto Papirologico <<G. Vitelli>> (Studi e Testi di Papirologia N.S. 2).

Smalley, R. 2012. Dating Coptic Footwear: A Typological and Comparative Approach. – Journal of Coptic Studies 14: 97-135.

Schwarz, S. 2000. Altägyptisches Lederhandwerk. – Frankfurt am Main, Peter Lange.

Sherpion, N. 1999. Sandales et porte-sandales à l’Ancien Empire. In: Ziegler, C. & N. Palayret. Eds. 1999. Lart de l’Ancien Empire égyptien. – Paris, Musée du Louvre: 227–280.

Vogelsang-Eastwood, G.M. 1994. De Kleren van de Farao. – Amsterdam, De Bataafsche Leeuw.

Wendrich, W.Z. 1999. The Word According to Basketry. – Leiden, Centre of Non-Western Studies.

Williams, B. 1983. Excavations Between Abu Simbel and the Sudan Frontier. Part V: C-Group, Pan Grave, and Kerma Remains at Adindan Cemeteries T, K, U, and J. – Chicago, The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago (The University of Chicago Oriental Institute Nubian Expedition Volume).

Winlock, H.E. 1948. The Treasure of Three Egyptian Princesses. – New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art[/spoiler]

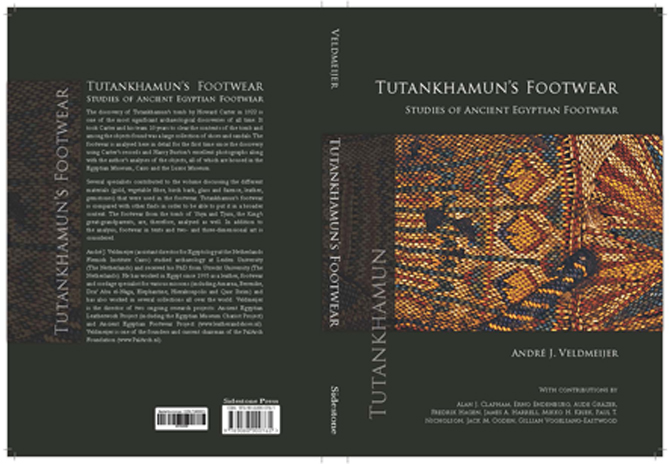

Book Presentation Tutankhamun’s Footwear [spoiler]

The book presentation was celebrated with a mini-exhibition “Archaelogy Meets Design”, with models of ancient footwear by Martin Moser and modern design by Jan Jansen.

2010. Tutankhamun’s Footwear. Studies of Ancient Egyptian Footwear. With Contributions by Alan J. Clapham, Erno Endenburg, Aude Gräzer, Fredrik Hagen, James A. Harrell, Mikko H. Kriek, Paul T. Nicholson, Jack M. Ogden & Gillian Vogelsang-Eastwood. – Norg, Drukware [part IX].[/spoiler]